Published by

SALTO Eastern Europe and Caucasus

Insights from the international seminar

Yuliya lelfimova, Dagna Gmitrowicz, Tomasz Szopa

11-16 July 2022, Toruń – Poland

Beside reading our article, you are very welcome to enrol to the open, online course

“Talking about war and peace. Facilitating learning in times of crisis” at the HOP platform.

With this article, we would like to share a collection of insights from the international seminar ‘How to talk about war’ hosted by SALTO Eastern Europe and the Caucasus in Poland in cooperation with the Polish National Agency of Erasmus+ Youth. The highlights harvested during this event significantly influenced our work as trainers and gave the solid basis for the upcoming online training module.

The context of the seminar

This seminar was unique in many ways:

- The participants were from the countries directly affected by ongoing or recent wars and armed conflicts (Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Cyprus, Turkey, Georgia, Croatia), and some of them were representing two sides of a conflict (Azerbaijan, Armenia and Turkey), but there were also participants from countries that recently have not experienced any kind of war (Denmark, Italy and Germany);

- The team of organizers was very diverse and complementary with the experience on the topic of the seminar, international and local youth work: the trainer from Ukraine Yuliya Ielfimova (a peacebuilder and a youth worker), Dagna Gmitrowicz from Germany (an artivist) and Tomasz Szopa from Poland (SALTO Eastern Europe and Caucasus);

- The location of the seminar was in the old Polish city of Toruń, where different organisations have been established in support of refugees from Ukraine.

The concept of the programme flow and its ground elements

The concept of the programme was built around the creation of a safe space to reflect on how to approach the topic of war with young people and youth workers, its consequences and how to be impactful. The specific focus of the programme was made on the context of the current Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The topic ‘How to talk about war’ was intertwined in the programme on three levels:

- I as a youth worker/trainer/facilitator – personal level;

- I and the others – facilitation of the learning process of individuals and groups;

- I and community – how to inspire actions as a youth worker/trainer/facilitator.

The ground elements which supported the learning process of participants within the seminar:

Addressing those who are interested in the topic. We believe that addressing people who recognise the complex situation of crisis during war and who are ready to talk, makes a bigger impact on societal change than addressing people who have no interest at all.

First building relations and later on going into the topic. Creating space for getting to know each other, focusing on the personality and uniqueness of everybody in the group, and highlighting the preciousness of diversity make a safe ground for difficult discussions.

Building understanding of the basic terms. War, conflict and peace – letting it remain different, not forcing one universal definition in order to avoid unconscious and unnecessary misunderstandings and still value every comment without judgement. The idea is not to work with the illusion of one truth, but rather to take into consideration more than one truth and harvest the discussions based on diversity.

Practising the culture of communication which is based on non-judgemental listening and empathy. This doesn’t mean judgements are not welcome, the natural aspect of the human brain is to judge, but rather to look at those judgements and let them go to open the space for deeper sharing and exchange.

Having a group agreement that is created and accepted by everyone. The agreement may come after the process of getting to know each other, earlier would be just an artificial set of rules, attitudes and behaviours.

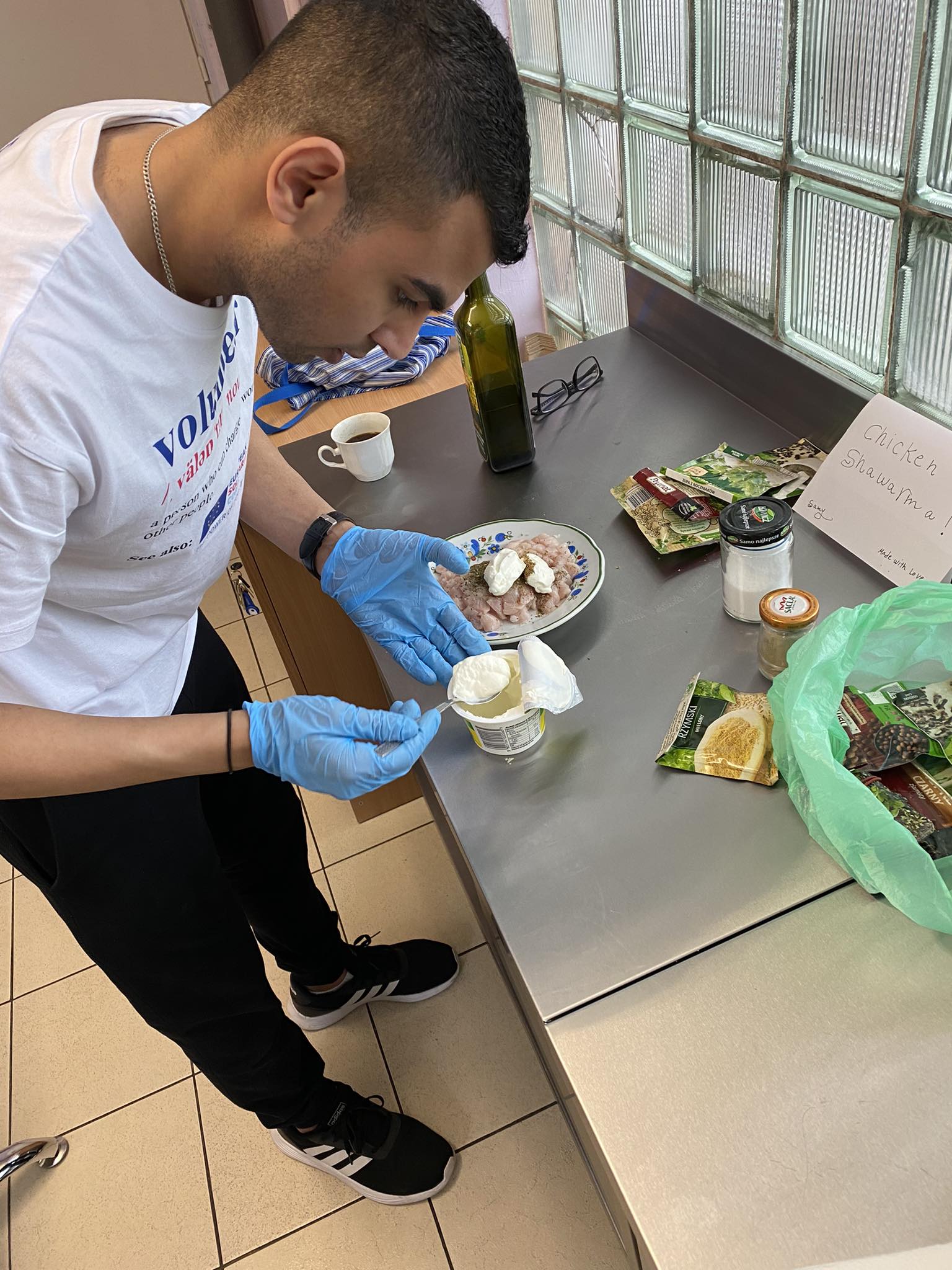

Encouraging thinking ‘out of the box’, by simply inviting participants to leave their comfort zone and face new dynamics in the topic of war and its crisis. In this seminar, during the study visits, participants were implementing workshops for refugee children as well as helping in creating a camouflage net which later on was sent to the frontier.

Using tools and methods of equally shared participation, e.g. way of council, focus groups, a fishbowl, open space, shared digital space to harvest all outcomes and tasks, accessible any time for participants (e.g. MIRO) – using the methods where everyone’s voice counts and is not forced.

Talking non-verbally e.g. using associational cards, inviting participants to the collaborative creation of the painting: transition of the image of war to the image of peace through collaborative suggestions; having space to reflect in a non-verbal way.

Strengthening different perspectives by applying such methods as tetralemma, debates, study visits, and a world-cafe.

Well-being of participants and embodiment: creating space for reflection, walks and tasks, outdoor activities, creating personal diaries for learning to harvest, energizers, and group playlists are used during the whole activity.

Peer support culture – meta reflection in smaller groups at the end of every day, we have called them: ‘How to groups …’. Where intimate discussions and sharing are taking place, and only chosen comments are reported to trainers.

REFLECTION QUESTION → What would be your qualitative criterion important in conducting this kind of meeting?

Overview of chosen methods and their outcomes

The terminology as a possible trigger of misunderstanding reveals the meanings of war, peace and crisis without pushing a universal understanding

Each person has his/her perception and understanding of such concepts as war, peace and crisis based on his/her own experience and background. It is important not to push the participants to come up with a universal definition of each concept but rather to show the diversity of opinions and perceptions. In this process, it is essential to highlight the appreciation of the experience of each and everyone in the group focusing on the realities of the participants:

What does ‘crisis’ mean in my reality?

What does ‘war’ mean in my reality?

What does ‘peace’ mean in my reality?

REFLECTION QUESTION → What would be your answer to these questions? If you answer them, check the outcomes of this exercise after our seminar. What have you noticed?

WAR in my reality means:

Military, opportunities, changes, unfairness, injustice, FOMO, no winners, vulnerable, not protected, propaganda, manipulation, fakes, pain, fear, feeling of danger, danger, irredentism, stigma, forced reality, war in media, hysteria, courage, loud sounds, destroyed lives, death, demonstration of power, blaming others for staying indifferent, distrust, loss, hate speech, violence against women, patriotism and pseudo, patriotism, denial, finding identities, the experience of getting above it, not to search for the other country, hate, uncertainty, solidarity, personal guilt to do war crimes and personal choice, economic collapse, political manipulation, reconstruction, trauma, fight, stigma, refugee, no home, courage, depression, stress, being in between different realities, a handicapped generation, lack of humanity, lack of human rights.

CRISIS in my reality means:

Irregularity, pressure, new realities, bad period, stupid substitution for the real term ‘war’, scapegoating, problem, a bad period, someone is provoking it and neglecting solutions, the term stems from the real term – aggression; strategies, resources, solutions, economy, inflation, government, lack of control, is not in our hands, going out of comfort zones, important to talk about, happens suddenly, something that does not work for you anymore, lessons learnt, egocentrism, differences, feeling nothing, surprises, eye-opener, medicine – lack of support, find like-minded people, bring change, action, opportunities, loss of faith, uncertainty, panic, emergency, deadlock, emotional sensitivity, hate speech.

PEACE in my reality means:

Personal well-being, being in peace with yourself, being loved and love, hope, relaxing and calm life, not being aggressive, no war, no terrorism, no evil, development, rediscovering each other, new opportunities (humanitarian, economic, etc.), being able to live my regular life, future, security, absence of violence and presence of social justice, acceptance of where we are at this point (what happened, the narratives), finding common ground and compromising, the importance of education, pacifism, stability, when others don’t care about me not to bother me, tolerance, diversity, identity, looking for better mental support, relying on positive narratives.

The way we talk matters over – you may avoid dead-end discussions by building a culture of empathy

One of the ways of doing it is to discuss and come up with an agreement in the group on ‘What is important for me to have effective communication?’ and ‘what is not negotiable for me?,’ – that is what we have to take care of during this meeting from the perspective of values, setting, self-expression, group dynamics, a trainer’s role. The contract-building process was preceded by getting-to-know exercises, empathic listening practice in pairs and the basics of non-violent communication.

REFLECTION QUESTION → What would be especially important to you, as a rule, that would help you safely work with others on such a difficult topic?

Reflect on your strengths, resources and coping strategies

Most of the participants were personally engaged in the topic of the seminar. However, it may happen that you as a youth worker/trainer/facilitator are not aware of the participants’ background concerning the topic of war. We should take care of the well-being of the participants during the educational event while addressing such a sensitive topic. For this, we should consider creating the space for the participants to reflect and explore their strengths in the form of coping strategies.

Coping strategies discovery:

Within the seminar, we invited participants to reflect on their resourceful channels in the face of crisis and trauma through the basic PH model. The participants went through the islands of coping strategies reflecting on the questions:

- If a belief is your ally, what do you do in a difficult situation? (B-belief);

- If feelings are your allies, how do you express them? (A – affect);

- If social networks and peer support are your allies, what do you do in a difficult situation? (S – social);

- If your imagination is your ally in a difficult situation, what do you do? (I – imagination);

- If knowledge, wisdom and facts are your allies, what do you do in a difficult situation? (C – cognitive);

- If your body is your ally in a difficult situation, what do you do? (Ph-physical).

The “coping strategies islands” were placed in the hotel on the ground, and participants could move freely from one to another and reflect on them.

REFLECTION QUESTION → What would be your coping strategy?

Sharing circles:

Personal stories need the attention of listeners and space. Personal stories of coping strategies in the situations of the crisis faced by the participants were implemented in smaller circles hosted by one of the trainers. It is important to notice, that we were not immersed in drama, but rather paying attention to mechanisms that supported participants to take part in this seminar.

The key principles of sharing were: talking from the heart, listening from the heart, no comments, no clarifications and keeping essence. Going through this practice created a space in the group of trust, safety and resilience, as well as enriched the participants with different coping strategies which they could apply during the seminar and in their personal and professional life.

REFLECTION QUESTION → Write down or share your story. What is your story representing your strengths and secret powers in coping with crisis?

Outcomes of coping strategies – best practices. How to cope?

- if we break our wings we should train our imagination;

- going running, cycling, hiking, yoga – everything that is connected with physical exercises;

- respect the moment that we could slow down;

- try to understand what is happening, ask people;

- I go to my own world of fantasy and strong belief that it’s all happening because of the reason;

- stay realistic and understand what you have the impact on;

- talk to friends and relatives, and try to reach out to your own community;

- by activities in social media;

- interaction with animals and nature;

- informational hygiene, cutting out digital communication (social networks);

- being connected to your beliefs;

- voicing, talking through the situation;

- being involved.

Pay attention to the community profile and its context

Time and again, we focus on the needs of the target group forgetting about the wider context and a local bias associated with a particular theme. During this seminar, we used the method of self-facilitated focus groups, which aimed to understand the needs and profiles of young people in particular cultural and political regions.

Questions to focus groups:

- How would you describe the general impact of wars on young people in your region?

- Who are stakeholders who influence young people in your region…?

- What are the most important needs of young people in times of war?

- What are the behaviours of young people?

- How do you feel yourself when you observe this, what is going on?

- Conclusions?

REFLECTION QUESTION → What would be your answer to those questions? Take some minutes to reflect on them and check the outcomes of the seminar.

Outcomes:

How would you describe the general impact of wars on young people?

- difference between experiencing trauma and war directly and indirectly;

- your whole world is affected but life goes on;

- fear, insecurity, aggression, hopelessness and feeling powerless;

- generally, changes one’s outlook on life: physiological problems, immigration, experiencing trauma changes your perception;

- fewer opportunities, education, lost time: life events, socialising, loss of experiences;

- affects the community: division, creating narratives of different social groups and nationalities, being labelled, a gap between generations;

- emotional loss and trauma;

- on education;

- barriers;

- violence.

Who are the stakeholders who influence young people?

- international community;

- government;

- institutions: education, religious;

- civil society;

- media;

- NGO sector, humanitarian aid;

- the community you live in;

- people who have experienced war, military, veterans;

- family;

- political leaders;

- youth workers;

- educators;

- celebrities;

- influencers.

What are the most important needs?

- entertainment: too much to think about all the time, a need for being young;

- knowing the truth;

- being Heard and Listened to;

- freedom: political, speech, actions, movement, to choose;

- adaptation;

- safety;

- accommodation;

- not marginalised;

- fun time.

What are the behaviours of young people?

- Support: from everyone, from stakeholders;

- safety and stability;

- basic needs: food, shelter etc.;

- help: psychological and social;

- migration: escaping from the active zones;

- black and white behaviour;

- egocentric behaviour;

- aggression, negativity, violence, criminal behaviour;

- desires to take action: military, volunteer etc. – just getting involved and engaging in war-related activities;

- unity: becoming more United, becoming proactive and creating communities;

- becoming an advocate for peace – solidarity actions, becoming a volunteer;

- bad habits;

- maturing earlier;

- panic attacks;

- violent behaviour.

How did you feel (yourself) when you observed this, what was going on?

- Shocked;

- Powerless;

- Self-organised, mobilised, being helpful and useful;

- Feel like a puppet, a political game;

- Fear;

- Scared, terror, horror;

- Regret, self-blame;

- Self-distancing: apathy, ignoring the reality;

- Helplessness;

- Responsibility;

- Aggression;

- Solitude;

- Hate speech;

- Powerless.

Final conclusions…?

- A need for belonging;

- Negative feelings;

- Life changing: loss of time and quality of life;

- Physical and mental scars;

- Loss of identity: hopelessness, shock, purpose, reinvent your life;

- Governments have a huge impact: they should try and minimise war impact and risk of war;

- Listen to the needs of young people, value youth;

- Secure basic needs;

- Prevents division between nations, communities, and generations;

Talking visually. The transition of the image and perception

REFLECTION QUESTION → How would you imagine the metaphor of a country in war? How would the war transform it? Which symbolic elements would add peace to this image?

During our meeting, participants were working with a visual metaphor painted in a huge format on canvas by one of the trainers. The metaphor presented the portrait of a blue skinned child with yellow tribal stripes on his/her face, half of the face was cracked like a broken stone. After the discussions in smaller groups and the new sketches were made by participants, the image turned over the night into a flying golden phoenix. Flowers, having covered the scars, were flowing out from under phoenix wings. One of the child’s eyes looked further. The image turned partly into a river that gave a new course, and a golden fish flowed out of the child’s mouth. At the bottom of the picture was written FREEDOM. A cracked skin seeped from under the flowers, wings and fish – the war left its mark forever.

This is the way how the image of the country in war was transformed during the seminar according to participants’ suggestions, it became a common metaphor for future peace:

Analysing obstacles in our own communities to address the topic of war with young people

To have an impact on our activities we need to understand the obstacles which we as youth workers face in addressing the topic of war in our communities. Taking into consideration the diverse background of the participants during the seminar we invited them to discuss those obstacles which they face in their communities in mixed communities’ groups. It created the space to see that the obstacles can be similar in different communities, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, to have a different angle of view on the obstacles in the communities which are affiliated directly with the war context.

The participants of the seminar identified the following obstacles which they face in addressing the topic of war with young people in their communities:

Propaganda and Disinformation:

- Creating a narrative;

- Creating the image of the enemy;

- Bias towards the majority of population, stereotypes, and generalising.

Lack of knowledge of a trainer/in the community:

- Lack of knowledge and experience in approaching people who have been directly affected by war;

- Do you have the right to talk about it if you haven’t been directly affected?;

- Trauma-prone topic and lack of experience using trauma-informed practice.

Psychological obstacles:

- Resistance of the youth to perceive reality,

- Traumatic experience,

- Seeking to continue with normal life.

Lack of involvement of young people:

- Lack of ownership in war-related process;

- Language barrier and different cultures;

- Lack of time for education or social work.

Political situation:

- Talking more about peace and options, but not doing anything;

- The political situation in the communities affected by war – state of peace or actual peace;

- Economic dependency and its influence on the communities;

- State policies related to the work on the topic, civic participation and freedom of speech;

- Artificial actions;

- Compromised security;

- Lack of funding for the activities which support dialogue, peace and conflict transformation.

Influence of the environment:

- Time and family influence;

- Social needs and support;

- Influence of the religious institutions on the attitudes in the society.

Sharing tools and working on collaborative solutions

Understanding that very often we cannot influence all of the obstacles due to our realities, however, we can intervene within the sphere of our activities and direct influence. The participants have chosen the obstacles they can influence and got involved in the discussion of searching for collaborative solutions of overcoming the obstacles through the “Fishbowl” technique.

Obstacle 1: Lack of knowledge

- Not to talk about conflict but to create content which unites, not the one that divides (workshops for young journalists). Topics about subcultures, music, food etc.;

- Creating opportunities by taking into account both sides of the conflict in a third, neutral country. Let young people experience peer-to-peer learning;

- It is easy to talk about war in countries that are at war but it is difficult to talk about it in a solution-oriented way, and extremely difficult to speak about the second side of the conflict;

- Lack of knowledge of the mistakes from the past influences current understanding;

- You can organise visits to countries/regions/communities to give people a new perspective. Visiting museums, local organisations, etc.

- Initiating picnics on different sides of the bridge (on the border) to open communication, discover each other and enjoy. Building bridges and crossing them together but not building walls.

- Quizzes on different topics in an engaging and playful way.

Obstacle 2. Lack of knowledge of a trainer/ in the community about how to work with trauma

- Networking and sharing best practices;

- Training for trainers with experts from the regions experienced with trauma-informed work;

- Online courses on how to talk about the war in the educational setting and a trauma-informed youth work;

- Inviting experts (psychologists, trainers etc.) to support the process;

- Listen to the participants – give them space to relax (sounds, relaxation techniques etc.);

- Using a trauma-sensitive approach as a background of training and stress reduction techniques;

- It is important to give the space for participants to be heard. In that sense, people would realise they are not alone.

Obstacle 3. There are such strong stereotypes that you can’t even speak about them.

- We need to establish a network and promote a new understanding. Being an ambassador is difficult but we need to find courage;

- As a youth worker, I am an example, I can’t be afraid of disarming the stereotypes publicly;

- Distinguish countries from people. We need to realise what we can do realistically. We could be in a good relationship and still see clearly what is possible. Sometimes we can’t take some actions;

- Link to local institutions which support young people;

- We talk about our identities. And we talk about conflict. How did it impact me personally, not having a political perspective but rather a personal one?;

- Be aware of what you publish on social media, for instance, pictures, the way you form invitations. In order for participants have a choice of what they can say when they come back. Give your participant a choice;

- Be aware of the time – when the war is not finished it is difficult to talk about peace;

- Give a voice to your participants and let them be heard on social media when they a have positive feedback. This way you empower people to make positive changes.

Obstacle 4. Bias and stereotypes concerning Russia lead young Russians not to participate in activities.

- Create extra activities only for Russians not bicommunal in the phase of open war actions.

REFLECTION QUESTION → How would you cope with the following obstacles: lack of knowledge, skills, hidden stereotypes and stigmatisation?

We had a lot of expertise within the group of the seminar participants. It was important to create the space where each of the participants had ownership of the process and the outcome. The Open Space technique was introduced to the participants to explore the topics, issues and experiences within the group to address the topic of how we can tackle the topic of war and be impactful. The topics were brought up by the participants through Open Space:

- How to use arts and art-based methods to work with the war-affected youth;

- How to educate refugee children who suffered from the war using non-formal education;

- How we can approach people who suffered from the war during seminars not to make them feel bad;

- How to work with young people affected by propaganda. How to talk to people who support the war;

- How to talk about the ongoing war with people who are not interested/involved. How to talk with young people who are not into the war topics;

- Reflecting on future dreams: imaginary future, society, building a common ground;

- What are the boundaries/limits for a trainer during training in war-related topics?;

- Starter kit on psychological first aid;

- Youth workers’ well-being working with young people affected by war;

- How to reflect on the past. Using movies to talk about war with young people living in a post-war society;

- When and how to talk about war during international projects. How to present/work with sensitive topics;

- Techniques of getting out from stressful training components.

Dilemmas appeared during the seminar – moments of uncertainty

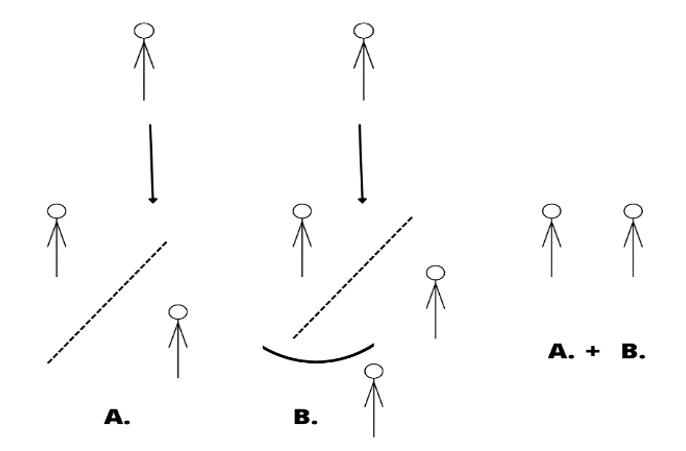

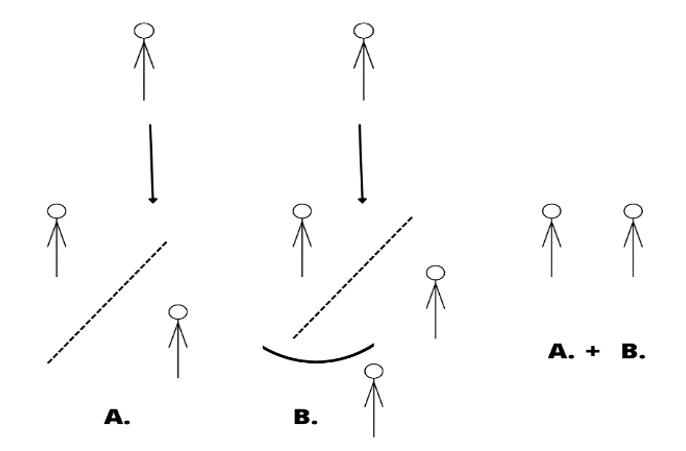

During the seminar, several dilemmas were brought up by the participants. The dilemmas came from the place of young people in the context of war:

- Group A: Young people who are directly affected by war (young people from each community, young people from both sides of the conflicting communities);

- Group B: Young people who are distant from war;

- Group C: Involving A+B.

Dilemma № 1: I should avoid talking about war with young people who support war.

Dilemma № 2: I should talk about war with young people even if they are not interested.

Dilemma № 3: I should involve young people in humanitarian response if they are not engaged with the topic.

Another dilemma related to the perspective of a youth worker/trainer/facilitator being engaged with the conflict and young people from two sides of the conflict:

How should we talk about war with young people coming from two different sides of the conflict?

We looked at this dilemma with the participants through tetralemma.

If we have two solutions to the question How should we talk about war with young people coming from two different sides of the conflict?:

- I should bring young people coming from two different sides of the conflict together

- I should work with two sides of the conflict only separately

Can there be any others? So, we built four corners of the Tetralemma:

- I should bring young people from two sides of a conflict together

- I should work with two sides of the conflict only separately

- A+B: separately and together

- None of the two: something different

The dilemma which was brought by the participants:

Can we talk about peace in times of war?

Conclusions

There are more dilemmas than answers when we explore the topic of war in the education process. Therefore, it was important for us to create the space of exploring the topic together, searching for collaborative solutions through mutual respect and understanding rather than giving ready answers.

The principles followed within the seminar:

- Seeing the individual and personality;

- respecting diversity;

- practising trust and empathy;

- mutual ownership for the process and the outcomes;

- respecting the experience of each and everyone;

- understanding that there is no eternal truth;

- creating the space of self-care and mutual support.

In this matter, the seminar itself was an example for the participants on how to create a learning process and the environment safe to talk about war.

REFLECTION QUESTION → What do you think? Can we talk about peace in times of war?

Useful materials

- How to talk about war. Facilitating learning in the face of crisis

- Resilience and Trauma – The BASIC Ph Model

- Self-facilitated focus groups

- Open Space Technique

- Teaching Strategies. Fishbowl

- Das Tetralemma. Ein Coaching-Tool für die Entscheidungsfindung von Dorothe Fritzsche

- Ways of Council. Circle Ways

- Building Bridges in Conflict Areas

- T-Kit 12: Youth transforming conflict

- SALTO TOOLBOX. Tools for Peace Education.

- Online course. Psychological First Aid for Children.

- Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide

- Receipts for Wellbeing,

- Controversial issues in the educational process. Teaching controversial issues (2015)

- 10 Tips for Creating a Safe Space

- We CAN! Taking action against hate speech through counter and alternative narratives

- I Support My Friends: A training for children and adolescents on how to support a friend in distress

- Creating Safe Spaces. A Facilitator’s Guide to Trauma-Informed Programming for Youth in Optimal Health Programs

- T-Kit 4: Intercultural Learning

- 256 Cards of Feelings and Needs.

- SELF-CARE MANUAL for Front-Line Workers

- Trauma-informed practice: toolkit